Anchors Aweigh

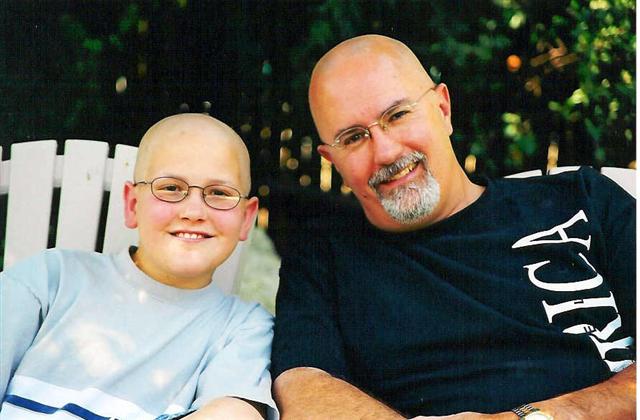

Yesterday my oldest son and his family packed up their household goods and began their move to Norfolk, Virginia, where, after five months of training in Groton, Connecticut, he will serve a three-year stint as an independent duty corpsman onboard the USS Albany, a Los Angeles-class, fast attack submarine. While I’m excited about the career development opportunity this assignment affords him (it’s the top of the duty ladder for corpsmen), and I know that it affords his family an opportunity to be close to his wife’s family in North Carolina and Maryland, I’m saddened by the loss of opportunity for those of us who are now in their rearview mirror.

I’m not a rookie at watching one of my children move away from home. Only one of our children still lives in our hometown and three of them have moved to distant locations out of state at one time or another. But this is the first time that one of the kids has left California and may not return. I’m trying to tell myself “that’s life” but it isn’t working real well. I’m also ignoring the fact that my wife and I plan to “move away” when we retire – but that seems like a different issue. Ah, the games we play in our heads.

My son and his family packed a lot of living in the three and a half years that they’ve been in California. As my daughter-in-law observed, they became a true family here, having moved here just a couple of years into their marriage and a couple months after their first son was born. While here they lived in three locations, including on the beach; they had their second son; they developed family friends as opposed to just personal friends; they established several family traditions; and they established a firm foundation for a successful military career.

And they also sent a husband and father to war. Maybe that’s underlying my sense of loss. The last time my son packed up to leave the State of California was on February 19, 2004, only six months after arriving in San Diego. Early that morning at Camp Pendleton I watched him board a bus filled with Marines being deployed to Iraq. I truly believed that he would come home safe and sound. But, lurking in the background was the inescapable fear that accompanies every departure of a loved one into combat. No matter what you believe, there are simply things that you don’t know with sufficient certainty. It’s the “may not return” factor.

As a father, I’m pleased that my son will spend the next three and a half years getting into a navy blue uniform rather than a green and brown camouflage uniform; and I’m pleased that his service will not just be on the water but underwater rather than on land. Deployment to sea duty doesn’t seem nearly as bad as it did when he last went to sea in 2000.

Like it or not, that is life for a family with a son or daughter in the military. Ultimately a family makes peace with the separation in no small part because that service is honorable and courageous. In Iraq, my son saved lives and he gave aid and comfort to men who lost their lives – honor, courage and commitment to duty. No small thing, indeed.

This feeling was reinforced night before last when my wife and I watched Flags of Our Fathers, the story of the three survivors out of the six men who raised the flag on Mount Suribachi on Iwo Jima. Two of those men lived troubled or unfulfilling lives. But one of them – John “Doc” Bradley, a Navy corpsman – exhibited not only courage under fire but a depth of character that sustained him and his family long after he left the black and bloody sands of Iwo Jima. I thought about my son and all of the other men and women who serve to treat, heal, comfort and save lives as corpsmen and medics in the Armed Forces. I’m as proud of my son as James Bradley, the author of Flags of Our Fathers, is of his dad.

It’s a good and noble thing that these men and women do. And they must leave home to do it. So, I wish my son and his family, “Fair winds and following seas.”

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home