The Unwinding Road

On the evening of March 11, 2002, my wife got a phone call from Danny’s oncologist in Los Angeles. He confirmed that not only had Dan not achieved a remission following his second relapse chemo protocol, his bone marrow was filled with leukemic cells. I sat beside her and listened to her ask questions that seemed to bear their own answers, and watched her make a few disheveled notes that would capture what had become an unavoidable conclusion.

Danny was going to die, in spite of 4½ years of courageous struggle through three rounds of intense chemotherapy, one round of moderate radiation, a final 39-day hospital stay that included unexpected kidney dialysis, and preparation for an awaiting bone marrow transplant. Her head was in her hand, and I could feel her heart break. It was the single most powerless moment of my life.

Finally she asked the inevitable question – how long? Three to four weeks she was told. She left the room to join Dan and his dad, who were in our living room. I left them alone for this most intimate of discussions, one that needed only the three of them. Most adults have experienced the wonder that attends the birth of a child. Far fewer, thankfully, have experienced the different form of wonder (and, yes, that word is appropriate) that attends the death of a child. My wife and Danny’s dad know what it means to have seen a child’s entire lifetime. There is a horrifying privilege embedded in that most unnatural fact.

As had been the case from day one in November 1997, Danny handled the discussion that night better than anyone else in the room. Unlike the rest of us, he probably needed no confirmation from a doctor or a batch of lab results. After all, it was just the day before this when he had extended an invaluable gift of profound comfort to his mom by assuring her with a single sentence. “I will be with you in your art,” he said. It was as if God had spoken from heaven.

Dan’s road from life to death taught me a lifetime of lessons about that road, lessons that continue to inform my life every day. I doubt whether I’ve even begun to grasp the extent to which they will inform my approach to death at some time in the future. As I write this I feel an urge to tell the whole story from day one to the end of days. But I can’t. It was an overwhelming experience that was lived out over more than four years, and that doesn’t include the grieving process that began as soon as Danny’s body was taken from our home. It seems like it would take that long to tell it. I will settle for dropping a few sentences, a few words, an allusion or two along the way, as if I were Hansel marking the path for my return from deep in the dark forest.

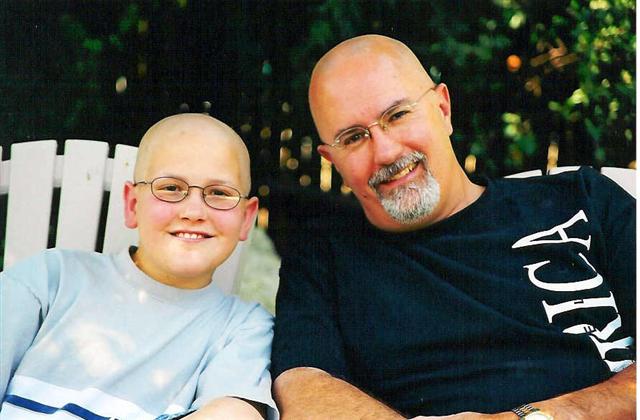

Today, I’ll focus on the one thing that returns to my mind time and time again with the mere mention of his name. For me, Dan elevated the word “resilient” to the pantheon of superior character traits. He was like a strand of that mysterious memory metal, the stuff you can twist, turn, bend and crumple, but when you let it go it returns to its original shape. In doing so, that metal reminds us that it knows its natural shape and it can regain that shape the second the rest of us let go of it. It’s only removed from that natural condition by others who twist, turn, bend and crumple it.

Leukemia did all that and more to Dan. But even that frightening disease could not hold him constantly. It might crumple him in its grasp for the few minutes of a bone marrow aspiration, or the few hours of a chemo infusion, which ironically left the taste of metal in his mouth. It might twist him during a wave of nausea or bend him in midst of a day filled with fatigue. It might turn his head as he passed a mirror and momentarily grappled with the bald head or the moon face. But this beast always had to let Danny go – and when it did, he returned to his natural state so fast that those around him would wonder if we had imagined what he’d just been through. How could he transition from gut-wrenching screams in the midst an excruciating bone marrow aspiration to laughing uproariously at The Simpsons – in 10 minutes time?

In moments like that my wife and I would look at each other and say, simultaneously and silently, “Who is this kid?” The answer is that in those moments he was all of us in our natural state – courageous; wonderfully resilient; filled with endurance and boundless capacity; and, most importantly, content to live in the present moment where freedom from fear resides. In those moments, Danny simply refused to let his mind take him to the past or the future, the twin domains of fear. Unlike him, most of us hardly ever leave those domains. Most of us never sense the moment when the beast in our life lets us go. Dan sensed and seized those moments like they were the air, water and food that sustained his life. Indeed, they were; and, indeed, they did.

As for the predicted three to four weeks – it was 3½ days. It’s rarely as long as we want; it’s never as long as we need.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home